The Gamer Words, gamer culture, and the real hate of an online world.

Jan. 6, 2021

by Corey P. Mueller

If you bought and played any video games in your free time this past year, you are certainly not alone. Video games were a common purchase; through November 2020, video-game sales were up nearly 25% (or $44.5 billion, with a B) year-over-year during the coronavirus pandemic. If you used these purchases to play competitive online games, there is a high likelihood that you have also heard some crass language in those lobbies. This includes but is not limited to racist, ableist, sexist and homophobic slurs; it is all part of the derogatory and insulting vernacular (which I will call Gamer Language, for now) that is pervasive and entrenched in the gaming world.

Particularly in this time of increased isolation and virtual community, we need to reckon with the hateful Gamer Language and its effects – it stretches beyond the confines of the online spaces we now inhabit from day to day. We have gotten used to interacting with other folks through screens, and this kind of communication is no longer insulated within gaming circles. The language used online, then, should receive the same scrutiny that it would in the “real” world, particularly in cases of hateful speech.

When a streamer (read: a professional video-game player) or a casual gamer drops the n-word while playing something online, it can be tempting for some to write this off as a thoughtless outburst during a “heated gaming moment.” Colloquially, slurs are shrugged off and labeled as “Gamer Words,” (the n-word is widely regarded as the ‘worst’ of the Gamer Words) deploying a diluted euphemism to ward off charges of racist intent. The following Twitter exchange from 2018 demonstrates this tactic, and it is one of the earliest examples I could track down of “Gamer Word” being used in a public forum:

Racist slurs are not new, nor is invoking irrelevant context to excuse bad behavior. Men have dismissed accusations of misogynistic language as “locker room talk” or “boys being boys.” We have seen a similar playbook used in the sports world; the Washington Football Team was formerly named an anti-indigenous slur, and the Cleveland Indians used a racist logo for years (which you can read more about in my previous post, Misanthrope Mascot); they were rationalized in the name of “honoring” indigenous people.

When members of the gaming community pad these words with the comparable misnomers of “Gamer Language” and “Gamer Words,” they dishonestly deflect criticism around behavior that, in any other situation, would be categorized as hateful speech that comes from a deeper place of dangerous ideologies and destructive worldviews. These would not be dismissed, but rather they would be taken at face value as bigoted language.

Some of the highest-profile incidents involving the use of racial slurs in the gaming community involve Felix Arvid Ulf Kjellberg, better known as “PewDiePie,” as mentioned in the screencap above. If you noticed a resurgence of Minecraft and Minecraft-related content on YouTube this past year, PewDiePie was largely responsible for this uptick. Kjellberg has the second-most popular channel on YouTube with 107 million subscribers and posted many high-performing videos with that game as their focus. Like many rich and famous folks, Kjellberg has had his share of what Wikipedia labels “media controversies.” In January of 2017, when Kjellberg had a lowly 52 million subscriber-count, PewDiePie posted a video that included a clip of two performers dancing in front of a banner that read “DEATH TO ALL JEWS.” Kjellberg solicited this clip from the dancers on Fiverr and specifically requested that message be displayed, and Kjellberg paid these performers for that clip.

That video has since been made private. In his apology, Kjellberg said,

“I’m not antisemitic, or whatever it’s called, okay so don’t get the wrong idea. It was a funny meme, and I didn’t think it would work, okay. I swear I love Jews, I love ’em.”

In this tepid apology, there is no demonstrable understanding of race, antisemitism, or the history of death threats toward Jewish people and the destructive outcomes that have spawned from these words and beliefs. His motivations were unclear but spreading a message that advocates for the genocide of an entire ethnoreligious group in the name of “jokes” relinquishes the social responsibility that comes with a cultivating such a large online platform. There is already fertile ground for hate crimes in this world (the United States had a record high number of antisemitic incidents in 2019, including a deadly stabbing during a Hanukkah celebration in a New York suburb), and popular internet stars have an added responsibility with an increased audience. Their reach is far, and they have a social responsibility to act appropriately in public, especially when there is a potential impact that reflects on young audiences. After the white nationalist and Islamophobic Christchurch shooting left at least 49 Muslims dead, the shooter released a manifesto that included references to Fortnite and internet culture, including a call to “subscribe to PewDiePie.” Kjellberg is not responsible for the mass shooting that happened in Christchurch, New Zealand, but it seems clear that the shooter has, at the very least, watched Kjellberg’s videos. At worst, the shooter identified in part with some hateful things PewDiePie has said in the past.

High-profile gamers continue to use this language seemingly without consequence, and this language becomes permissible among low-profile gamers in the general populace. According to a 2019 poll from Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Technology and Society, 65 percent of online gamers have experienced “severe harassment”, and “74 percent of online multiplayer gamers have experienced some form of harassment.” Unfortunately, PewDiePie’s controversies did not end with antisemitism; Kjellberg said the n-word while playing an online multiplayer shooter called PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds in September 2017. Kjellberg also posted and consequently deleted an image that mocked singer Demi Lovato’s drug addiction. Often times, like PewDiePie in his apologies, online harassers will hide behind the guise of making a joke or “doing it for the meme.” “Antisemitic, or whatever it’s called” or not, hate-speech-as-meme circulates regularly on the internet, which creates a self-reinforcing cycle of casual bigotry.

Hate speech and its consequences are not new in the United States – the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project gives a more comprehensive overview of anti-black racism’s history in this country – but it is an ever-shifting behemoth that finds new ways to be “acceptable” in popular culture and our society. Giving it the mask of “The Gamer Word” does just this – it codes the language and softens how we perceive its use. Calling it “The Gamer Word” also concedes that this is just a thing that happens in online spaces during video games and does nothing to challenge the norm. That norm, of course, should be challenged in the name of anti-racist pursuits. Racism is not the only form of bigotry found online; the GamerGate saga, for example, demonstrates the dangerous misogyny that is also alive and well within the gaming community. Racism, however, comes up time and again, and is unfortunately not a thing of the past.

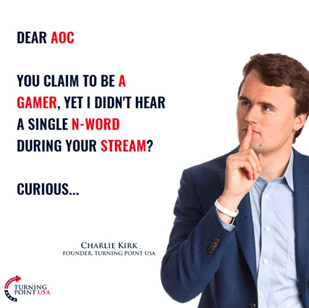

In October, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez jumped on the streaming website Twitch to play the uber-popular multiplayer game called Among Us. Shortly after, someone I know sent the following meme to one of my group chats:

This joke relies on the common understanding that racist slurs are used regularly and openly in online gaming. Charlie Kirk serves as the punchline because he, like the tweeter defending PewDiePie, interprets the use of racial slurs as an in-group identifier rather than an expression of racial animosity. This is an argument that relies heavily on someone being “offended,” and it is an attempt to discount the “feelings” of someone on the receiving end of racist language.

The problem extends beyond simple offense-taking in Call of Duty lobbies or Reddit threads. According to Boston’s Childrens Hospital, “children targeted by racism have higher rates of depression, anxiety, and behavior problems” and “when asked to recall a racist event they’d witnessed as a child, young adults had stress responses comparable to first responders after major disasters.” Around 20 percent of gamers are under 18; gamers and content creators are exposing children in their formative years to ideas that have been shown to inflict harm on their communities. I do not know if my pre-pubescent teammates understood the gravity of what they were saying during a Valorant match a few months ago, but it did not stop them from yelling the n-word back and forth in team chat. I am certain that they believed themselves to be “edgy” and found some sort of humor in using that word. I am also certain that they knew they should not be saying it, because one of them would only say the first half of the n-word, and the other would finish the other half. This has led to some of my friends instantly or automatically muting voice chat in various multiplayer first-person shooter games.

Without some sort of oversight or intervention, this is how society perpetuates and allows racism on an individual level. Riot Games, Blizzard and other large gaming studios claim they advocate against racism, but they fall short on effectively banning folks who use this kind of language, even they have more than enough resources to create a systematic solution for these bad actor individuals. The scope of systemic racism reaches far beyond an individual’s actions and racist behaviors, but it is a feedback loop. Without challenging these behaviors, the young and impressionable folks (like 11% of PewDiePie’s audience who are between 13 and 17 years old) who dole out these slurs become young adults who do not believe in systemic racism, nor do they believe that racism is a problem. This cycle keeps replacing the bricks that uphold racist and hateful foundations, and the damage continues to be wrought on vulnerable communities within that system.

Framing hateful speech as quotidian among gamers does real harm; the laughter of self-proclaimed “dark humorists” does not offset the damage of bigotry.

I hate to be the joke police, but I have developed a simple (and I believe very reasonable!) rule for jokes: jokes are supposed to be funny. I do not believe this is a high bar to clear for joke-tellers, content creators or recreational gamers. What, then, is funny about dancing in front of a sign that advocates for killing Jewish people? What is funny about drug addiction, specifically when a public figure is *publicly* sharing their fight against that disease? I may be called overly sensitive for these stances, but there are situations in which sensitivity is necessary for the health and safety of people who are vulnerable and/or part of marginalized communities. A friend of mine posted the following “meme” that I find more true than funny in one of our shared Discord servers (Discord, for the uninitiated, is like a fun version of Slack. There are different chat rooms and servers you can join to pop in and hang out with friends or game. It is a social medium designed specifically around gamers, but it has other uses as well.) I find this applicable to a not-insignificant portion of content I find online:

When a joke relies on hate speech as the punchline, it is lazy joke writing and harmful to folks not insulated by privileged identities. If you need examples of this, I will point you towards the MISFITS, a group of Australia-based content creators comprised of Australian and American YouTubers. Sometimes they are funny! Other times they come just short of saying the n-word or prod at an “n-word pass” or flat out say the slur for the giggles.

There is no reason to defend these words and this language, nor should we continue to accept them in our online spaces. Gamer Words need no protection nor are they under any threat; streamers with millions of subscribers live comfortably and have the privilege of entertaining audiences with video games. They need no defending. Marginalized and ostracized people targeted by this prejudiced and abusive language, however, deserve our fervent defense in the face of Gamer Words.